William Keble Martin Lily Illustration

by Ashley Eyvanaki

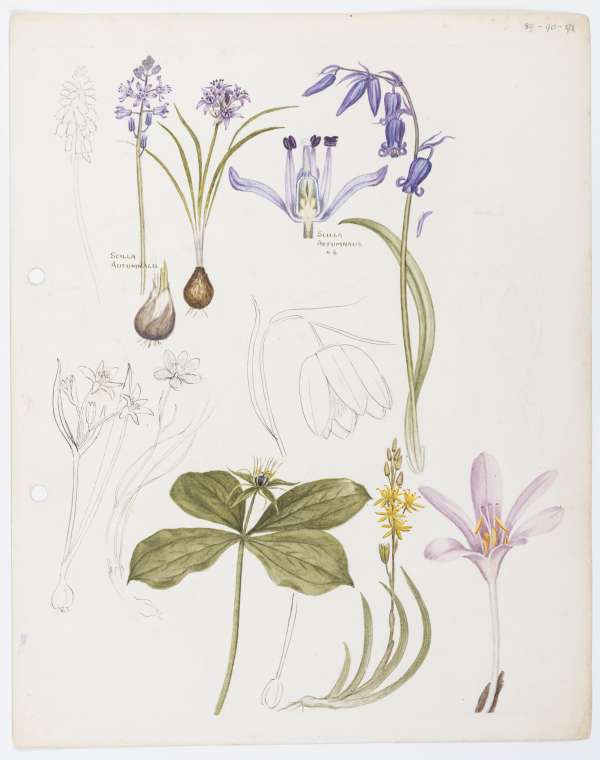

Lillies by William Keble Martin (RAMM Collections)

Have you seen William Keble Martin’s illustration of flowers in the lily family? The Reverend spent much of his life studying plants and capturing their likeness in sketches and paintings. In 1934, his work took him to the vicarage of Great Torrington, where he devoted his energy to visiting parishioners and preparing sermons. However, his free time was spent in the garden and nature, studying botany from real life. For example, Martin drew the meadow saffron flower or Colchicum Autumnale seen in the bottom-right corner of the illustration from life, basing it on a specimen found in Torrington. This illustration of flowers in the lily family was a preliminary plate to be included in his book The Concise British Flora in Colour, which was then published in 1965.

Historically, lilies also hold significant meaning within the LGBTQ+ community. For example, the floral paintings of artist Georgia O’Keeffe have widely been thought to have a dual meaning. In particular, her delicate paintings of calla lilies have been viewed by some art critics as an intimate depiction of the female genitalia, so have been repurposed into an erotic lesbian symbol. During the 1970s, a new wave of feminists began to celebrate O’Keeffe’s portrayal of nature, the body, and themes of gender, despite her neither encouraging nor discouraging such interpretations of her work.

By 1999, artist and activist Michael Page suggested that the trillium flower be used as a symbol of bisexuality. The flower is significant as a member of the lily family, as well as for first causing scientists to use the word ‘bisexual’, albeit in reference to them having both male and female sex organs, rather than in reference to sexual orientation. Page wanted to create a prominent symbol for the bisexual community, much like how the rainbow gay pride flag had become emblematic of the gay community after its creation by Gilbert Baker. As a result, the bisexual pride flag consisted of a pink and blue stripe, with the former representing homosexuality and the latter representing heterosexuality, with both overlapping in the middle to form a purple stripe that symbolised both sexualities becoming one. This flag design emblazoned with a trillium grew to be widely accepted across Mexico by 2001, intertwining themes of nature with bisexuality.

What is your favourite LGBTQ+ flag design? Tell us in the comments below.

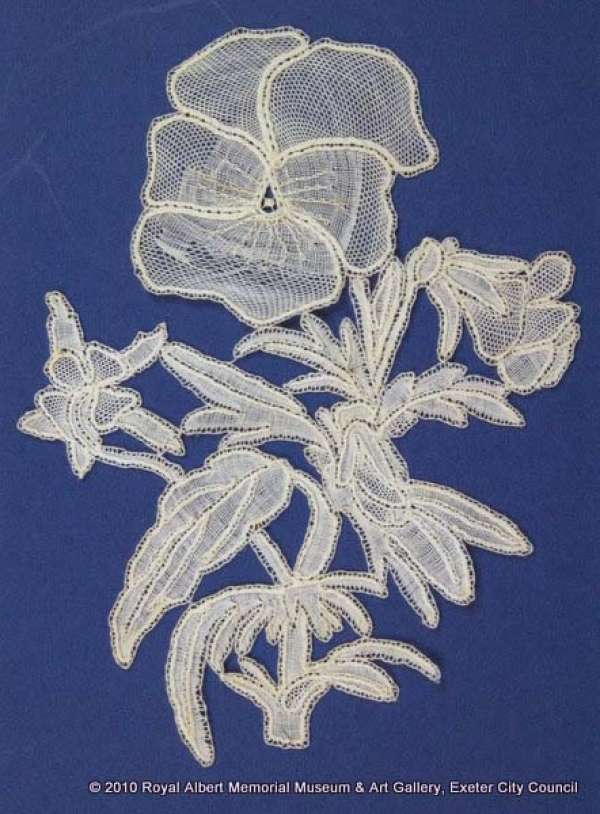

Honiton (East Devon) lace sprig

Honiton (East Devon) lace sprig

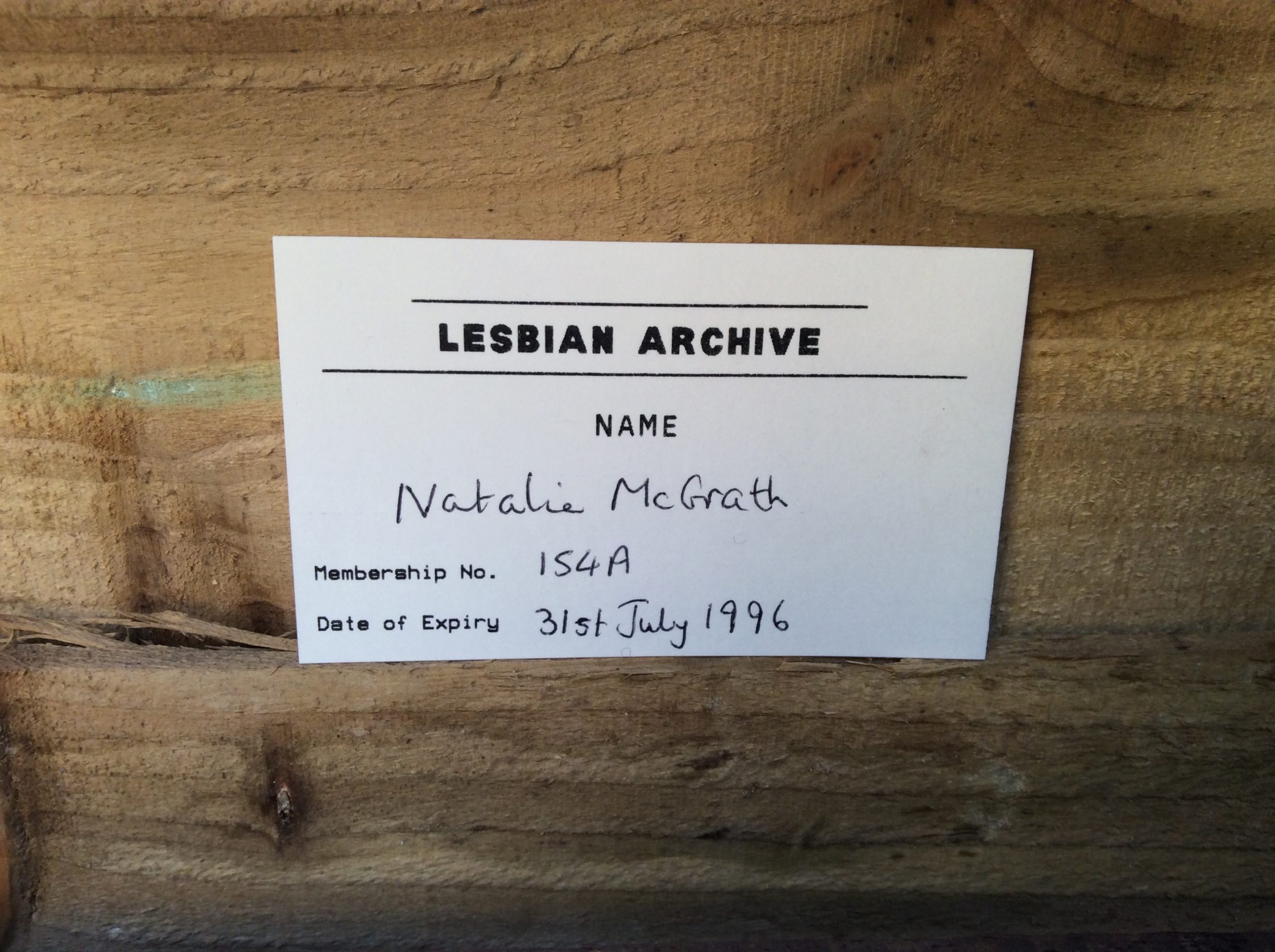

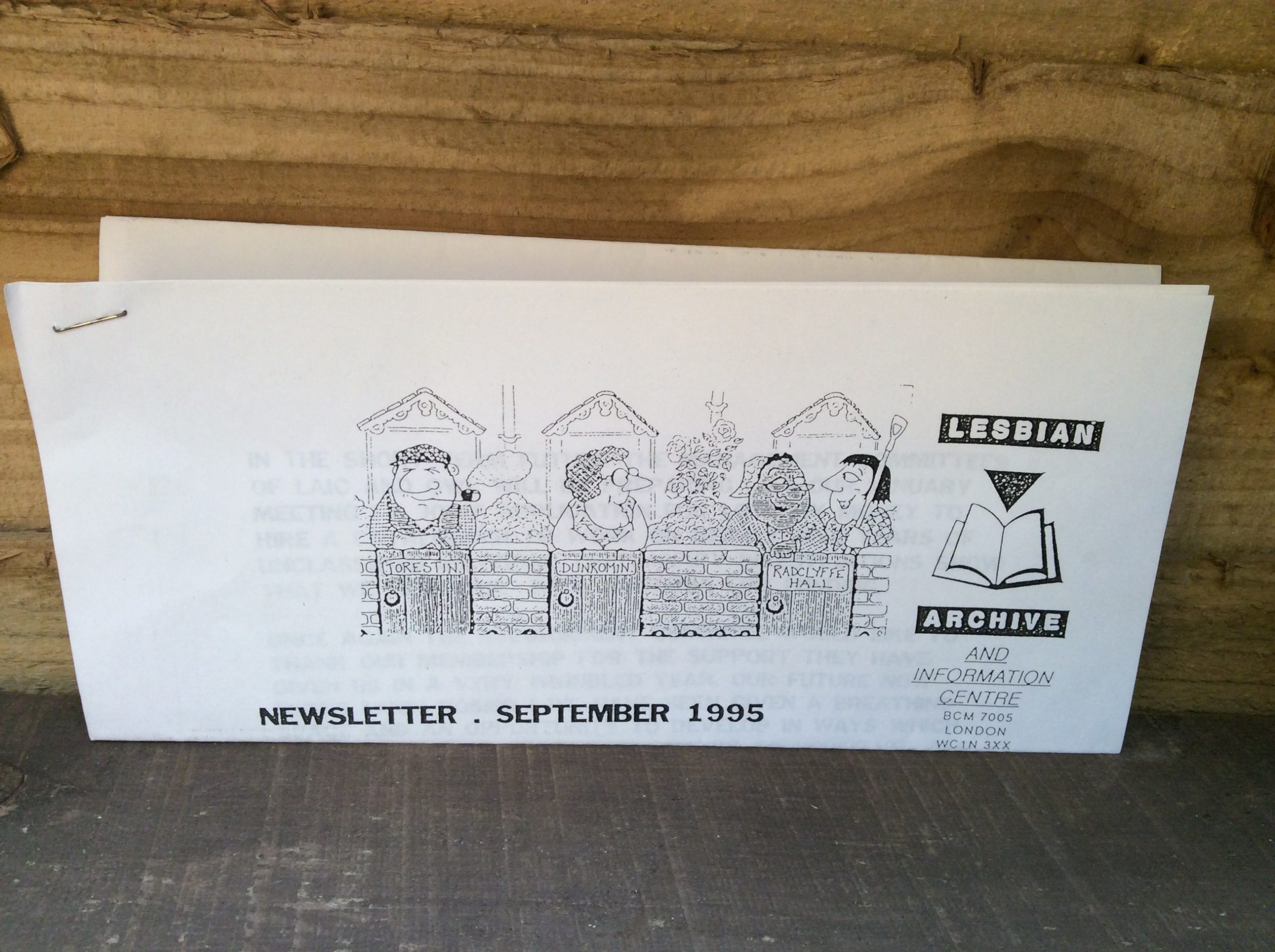

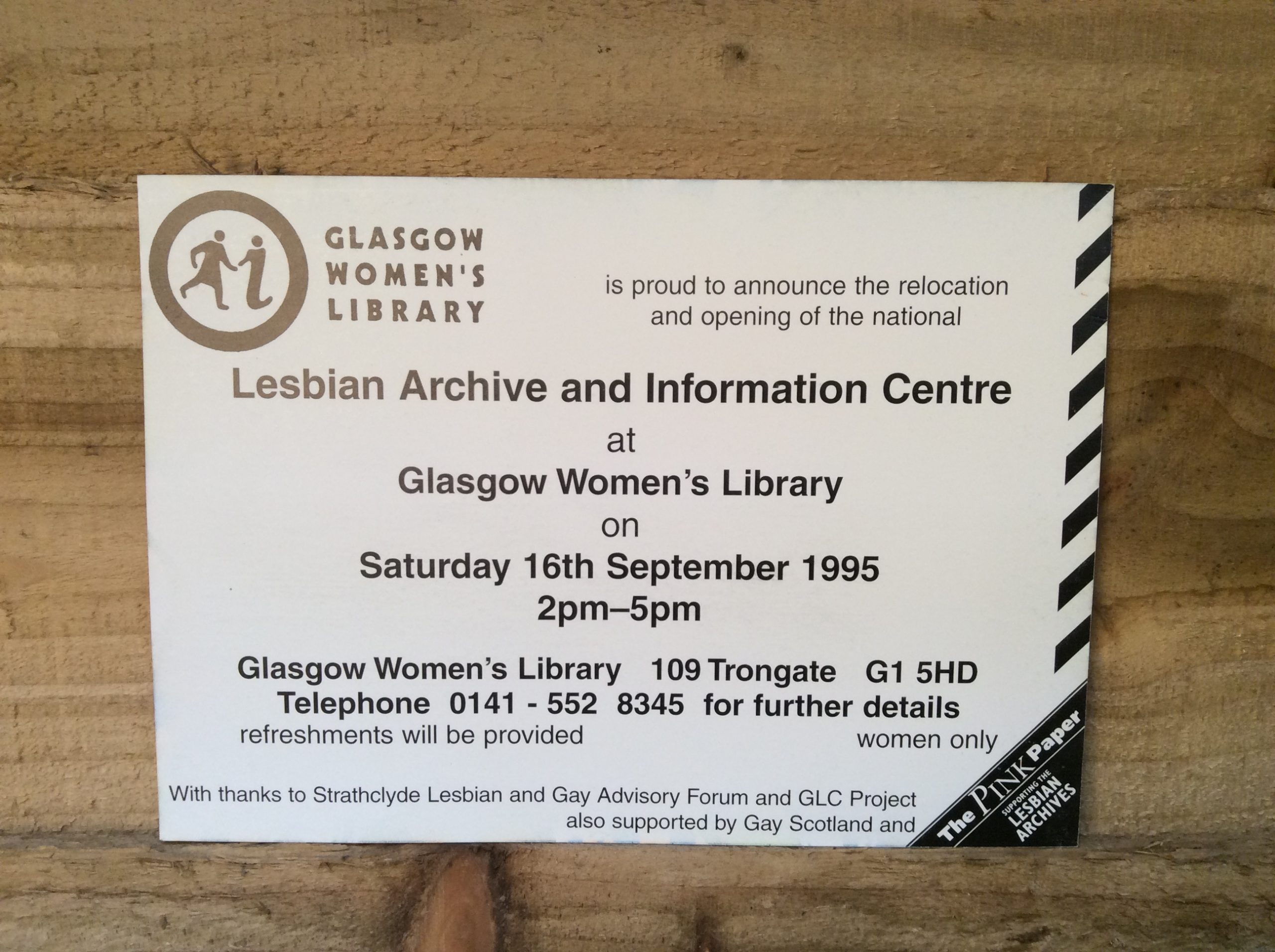

In 1995 I visited LAIC as it was beginning to pack up its collections and relocate to Glasgow Women’s Library. I had just finished my second year as an undergraduate and was beginning to research for my dissertation.

In 1995 I visited LAIC as it was beginning to pack up its collections and relocate to Glasgow Women’s Library. I had just finished my second year as an undergraduate and was beginning to research for my dissertation.

These moments that I have joined up mark somewhere my own identity and queerness as a lesbian. As I get older and look back I understand the vitality of these collections more and more and funnily enough in a way it has probably led me to here. To this current wave of work I am doing queering the museum and the oral stories that will follow and become part of a permanent collection at RAMM. These pivotal fragments are emotional ones. It clearly struck a chord back then as well as now and these objects are something I have kept, preserved and valued for 25 years now.

These moments that I have joined up mark somewhere my own identity and queerness as a lesbian. As I get older and look back I understand the vitality of these collections more and more and funnily enough in a way it has probably led me to here. To this current wave of work I am doing queering the museum and the oral stories that will follow and become part of a permanent collection at RAMM. These pivotal fragments are emotional ones. It clearly struck a chord back then as well as now and these objects are something I have kept, preserved and valued for 25 years now.