In late 2021 and early 2022, Natalie McGrath and Jana Funke interviewed 20 LGBTQ+ people (including themselves) about objects in the RAMM collections that resonated with them. Our project collaborator Stand + Stare designed a beautiful interactive installation to share extracts from the interviews with RAMM visitors. The interactive was launched during LGBTQ+ History Month in February 2022 and is on permanent display at RAMM. If you cannot visit the museum in person, you can listen to (or read transcripts of) the extracts as well as the full interviews below.

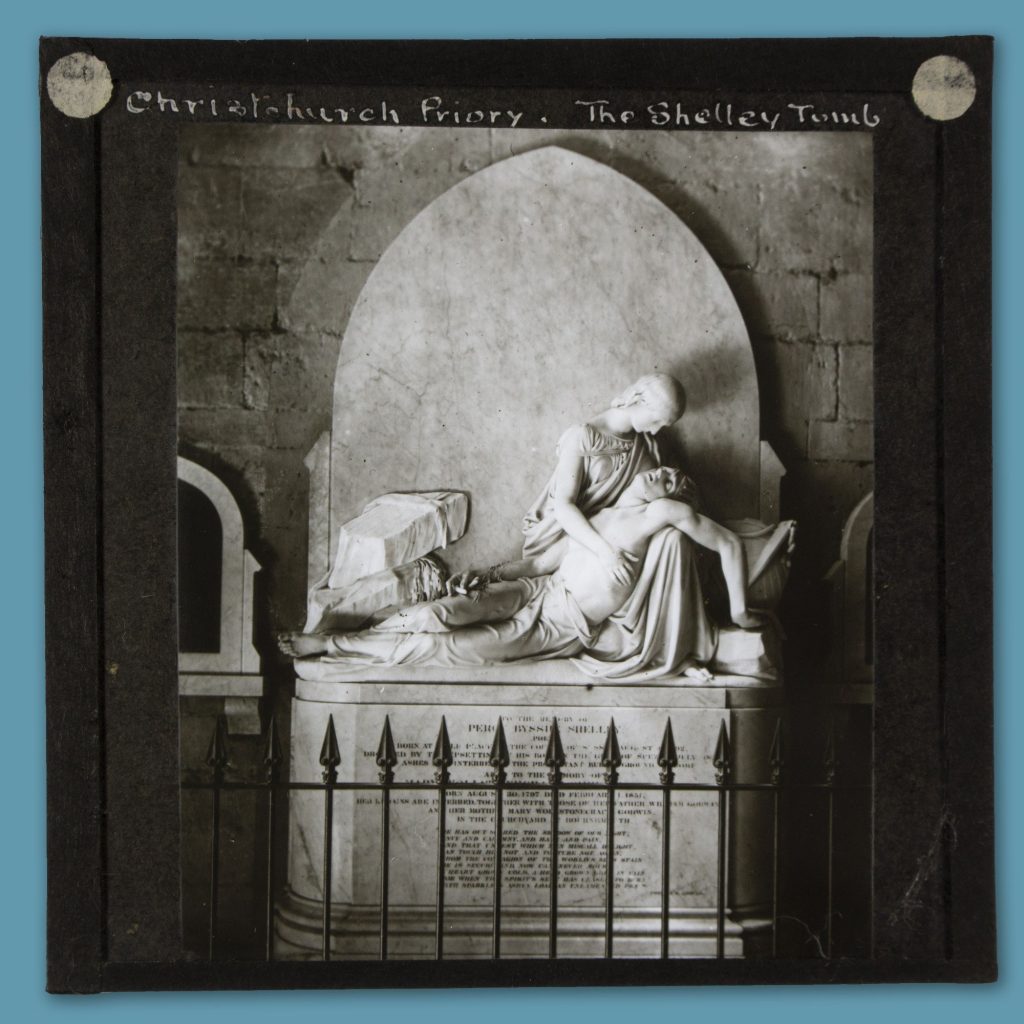

“It’s a photo, or it’s a slide I should say of the Shelley Tomb that was commissioned by Sir Percy Shelley, one of Mary and Percy’s surviving children. … There is so much queerity to the Shelleys and to their romantic circle and to Frankenstein on both a literary level and the kind of legacy of Frankenstein as well. Victor Frankenstein as a queer figure. I read him as both transmasculine and transfeminine, and I just remember relating to him so heavily, I remember him being a trans hero for me. … And then there’s also the inherent, I think, transness of creating life whether that be kind of self-determinant or creating life, you know, for someone else. … There is an absolute joy in self-creation and self-determination even if you are told there is not.”

“So, the object I have chosen is a taxidermy luna moth. I have a tattoo of a luna month on my right forearm, and I think it just really connected with that and the way that I feel I’ve been able to use tattoos as a way of reclaiming my own body so it really resonated with that. There’s just something really lovely about, I think, as a trans non-binary person feeling very disconnected with your body, being able to use tattoos, it’s like a form of visual art to kind of reclaim that space of your body and kind of reconnect and be able to fall in love with your own body in that way. … And there’s something about being viewed as one thing but being something else that, I think, really speaks to me a lot. And I think again with the luna moth they are kind of often assumed to be butterflies but are actually a moth, and I think it connects to a lot of personal ideas of my queerness and gender and how you relate and how the world relates to you as well. Often there are narratives that use butterflies and caterpillars as this kind of visual narrative for transness, and moths as an alternate version of that; [it] is this less-clear less-linear what-is-it vibe.”

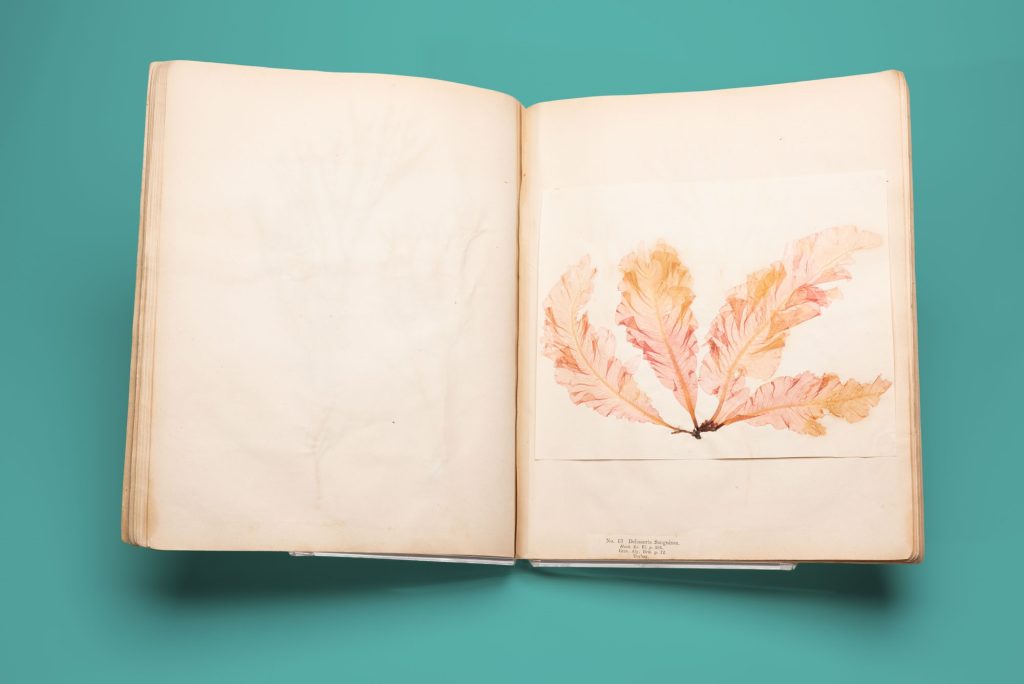

“The object that I’ve chosen are the volumes of pressed and named seaweeds. And they were published in 1833 by Amelia Warren Griffiths and her companion Mary Wyatt. So these two women, kind of, the thought of them combing the shores of Devon, which has been my home now for over 20 years. The fact that these two women created something really beautiful together whether they were in what we would determine and categorise as a lesbian or a sexual or romantic relationship, it actually doesn’t matter in terms of the context of this labour of love that they created together. … You know, the beach and the sea and that part of being in Devon and actually just standing and maybe being held by water, being held by that rhythm of the ocean. … There’s always more than one story and that we have to move away from those dominant narratives that we keep getting told in terms of who gets to tell history or who gets to choose what goes in a museum or who gets to label it or and what that object could mean.”

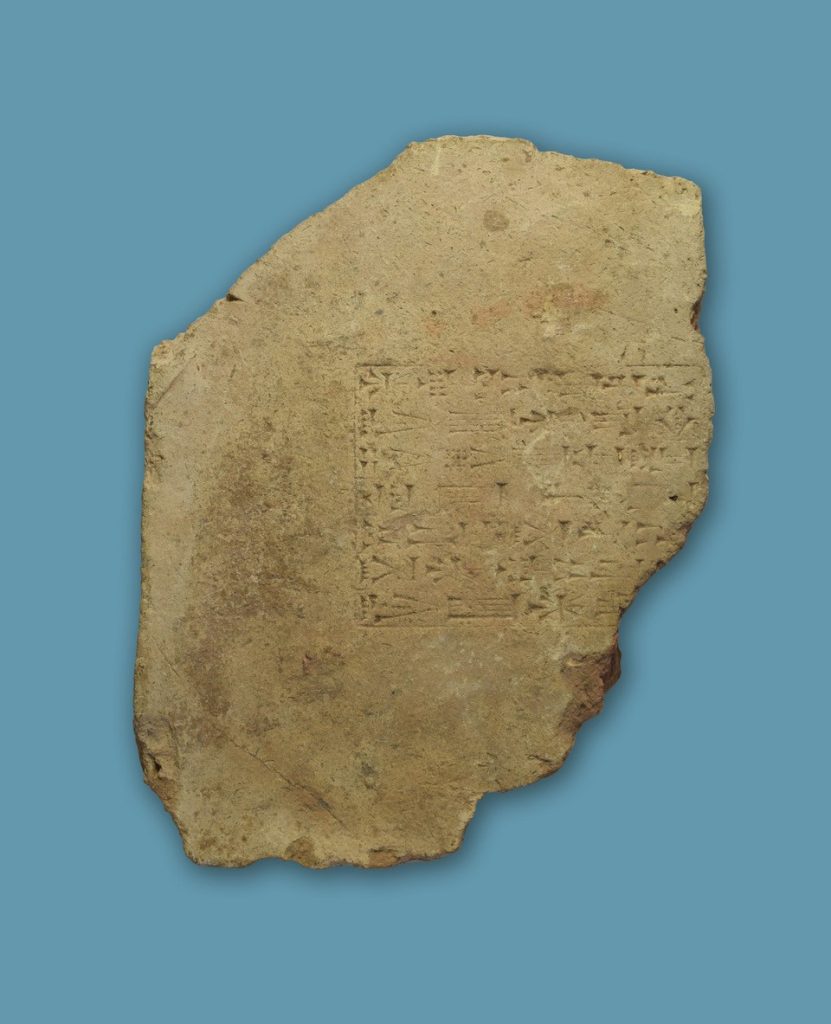

“It’s a brick from the Mesopotamian period. It’s believed to have come from Nebuchadnezzar’s palace in Babylon. There’s a cuneiform inscription on it. … I was drawn to this object, because I was looking into Mesopotamia and ancient Babylon, particularly their worship of the goddess Ishtar. And Nebuchadnezzar, he was the master, the Emperor of Babylon for a period of time, and he built the gates to Ishtar, which is this huge, fantastic monument. And I was interested in the goddess of Ishtar, because she has a lot of worshippers and specific cults that worship her who are, who identify as gender nonbinary, and a lot of the worship of her actively encouraged people to be nonbinary, to identify outside of the gender binary. And I just love that thousands and thousands of years ago, about 3 millennia BCE, people, gender non-binary people, had a space in society, and we’ve always been here, this isn’t a new fad now, it’s … we’ve literally been around for thousands of years and had a place in society. And I just love the idea of being able to turn around and being like, look, queer life has always been here, and it’s been peppered the whole way through, and we can all find things that chime within us … find your story within these objects.”

“I’ve chosen a lovely drawing by somebody called Piper of the Quay in Exeter. It’s just a beautiful drawing of the Custom House. Now, I have an association with the building to the right, not the Custom House, the one across the road, that was the nightclub that I used to DJ at in my younger days. That’s where the LGBTQ+ night was held, the very first one in Exeter, it was called Boxes on Tuesday. … A lot of LGBT people will identify with that picture, probably of a more senior age now – not that long ago, I am talking about the 70s and 80s. That night was never publicised back then; we just couldn’t. It was just not safe enough for people to make it public that there was an LGBT night there. We still banned cameras so we’ve got no photographic evidence of anything that ever happened in those nights. It was like a secret nightclub; it was just a fantastic place for LGBT people to meet, the biggest secret in Exeter probably. … It was life-changing to just go into that building and be with other LGBT people. It’s really important to me, and I know it will be important to a lot of LGBT people just to see that building and say, wow, that’s where I was able to be myself, and it was so important in my life at that time.”

“The proper name of the object is St Peter trampling the Devil. I thought it was a kind of a little bit homoerotic, because, well, it’s just the fact that this guy is squishing Satan with his foot; he’s got his foot on his body, on his naked body as well, and Satan is looking really angry, or the devil or whatever he’s called, is looking really angry in this, and Saint Peter is not even looking at him, he’s just looking at his book, he doesn’t even seem to be aware that he’s stood on this devil, and there’s just something about the power play in that. … And also the fact that there’s this intrigue around it, of where did it come from, and the idea is that they think it was probably made by an immigrant, someone from France or Germany, or the low countries it said. … It’s really easy to look at, you know, something from five hundred years ago and not have any connectedness to that person or the people who lived then, and not think about them as having gender identities or having any kind of sexuality, so, yeah, I think it’s important for those reasons.”

“I have chosen a small ceramic figurine; it is of a headless person nursing two children … the Dea Nutrix. For me it isn’t also just about babies, it’s about bountifulness and caregiving, which any woman is able to be. It doesn’t mean that only heterosexual women have that. … But I do think there is too much stigma and judgment about whether women have babies or don’t have babies and what that makes you, whether that makes you a good person or not a good person; whether you are a good mother or not a good mother. And in a way just making a figurine that is a small representation of love, actually, and care and nurture is something that I want to claim, but I think every woman has a right to claim it, too. … Celebrating that uniqueness rather than conforming to one idea of what we are as a human being. I think that’s the last thing I wanted to say about this object. It was for me about nonconformity, and not staying with the accepted, you know, culture of what we can be and what we are.”

“It’s a big old bowl dish and an amphora jug from ancient Greece. … Ancient Greek culture was particularly tolerant of queer relationships that span gender identities, and it wasn’t at all unusual as we know for men, and sorry to be a bit patriarchal about this, but it was still a society that was largely organised around male power, for men to be married, to have families, but also to have, you know as we know, male lovers and so on. And obviously, because I identify as bisexual this kind of speaks to me. … Throughout my general identity, but also within my queer identity, I really thought about the importance of places where we eat, and particular drink together, and how having those places and having those people around me has been so, so important. This is why people love festivals, and it’s those kinds of opportunities to come together, but also where some of those normal labels don’t matter so much, you know we just kind of enjoy the basic humanity of we all need something to eat, we all need something to drink. … So, I think if Doctor Who shows up, I’m almost regardless of which part of history I land in, I’m gonna be all about the food and the drink and the people.”

“The object that I have chosen is a coffin pall. This object was repurposed from priests’ vestments to a coffin pall during the reformation. … I’m a Catholic, so it has always resonated with me as being part of my faith’s history. I think I’ve also always really admired the resourcefulness of this parish community, that they had these beautiful vestments, and that rather than lose them, they sought to repurpose them. … I think it made me think about the relationship between my own faith and my sexuality. Obviously it’s often really difficult to be a queer person within church communities; I think, we’re all well aware of how hard that can be, but for me personally at least, it has sometimes also felt difficult to be a person of faith within queer communities. … So, I don’t want to speak for everyone, but, yeah, maybe for any queer person of faith who has felt that tension between those two parts of themselves, or anyone who has felt like they’ve had to remodel any part of themselves in order to feel that they fit more easily in the world, then, certainly I feel like there could be a point of connection there, definitely.”

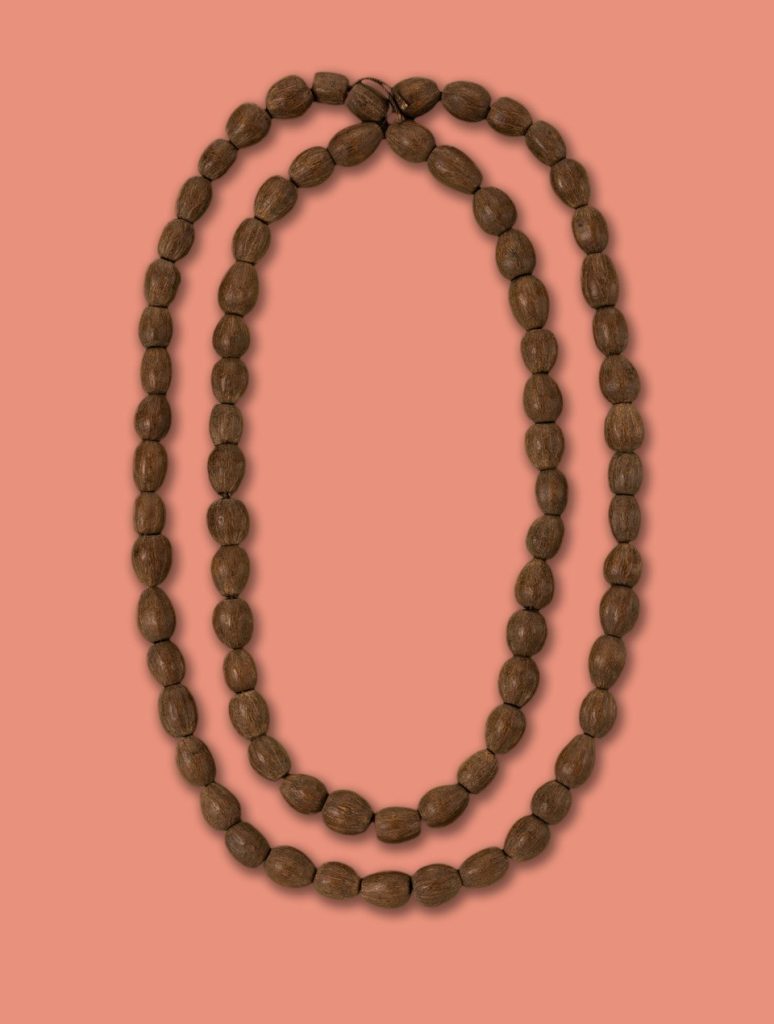

“So, I’ve chosen this set of Islamic prayer beads that comes from Sudan, but the thing I find most fascinating about it was that it has 78 beads which – for those that aren’t familiar with Islamic practices – most Islamic prayer beads have 99 beads or a multiple of 33. After a while, I ended up counting the beads and going OK, there are 78 beads here, this is not right. … That object, the part of why I connect it to queerness is the sense that something has been missing and that hasn’t been noticed. … I think on a broader level a lot of our conception of queerness is very white, it’s very influenced by Western cultural values. … I would like people to know that there are many histories that they are not aware of, and those histories are very rich, and I find myself very reassured and grounded by the idea that there is a track record of people like me that stretches back for hundreds of thousands of years. … History as collected in the museum is active and it’s constantly being written, and the way that we look at the same object will change over time and that’s a good thing.”

“The object I’ve chosen from RAMM’s collections is a collection of sand samples by a poet called Ivor Treby. It was quite moving to actually see these sand samples that he collected his whole life, and it occurred to me in seeing them that it felt very much that they were almost like his ashes; they’re not literally his ashes, but they are this granular material that Treby left behind. … With Treby’s sand there’s both the strata and the layers that all of us have, and perhaps as queer people we feel we’re more aware of our layers sometimes. And some of them can be challenging and some of them are wonderful, but we kind of become more aware of our strata and a kind of scattering. And sand, of course, is a great one for scattering, and that we can feel, I think, quite scattered, particularly over the pandemic we felt very scattered. We haven’t had our shared spaces, but still kind of find ways, I think, as queer people. So, it’s a wonderful metaphor for lots of things – sand – and maybe Treby knew that; he was a poet. I think there’s an organised playfulness to what he collected and maybe a queerness to that. … I hope that it will give people that sense of some objects that reached a hand across time and across generations. Treby himself connected with his elder queer people. They travel across time, connect us to him and his journeys.”

“The object that caught my eye is a hand-held mirror with wooden handle, and it’s an Egyptian mirror. It’s old, it’s a little bit rusty, but it looks like it’s been loved. … Whenever I go to museums, I always look for something that feels like it’s close to home, and home is the Middle-East, and so I looked at the North African and Middle East Collection. … There was something about the gaze, but the gaze was inverted. because it’s about – you are looking at yourself in the mirror, but also imagining who would have looked at themselves at the time. So, it would have been primarily used, I imagine, for vanity, and there is just something really human about checking yourself out in the mirror before you leave the house. … There is something about being introspective when coming out happens, right, for you, if you’re a queer person, because it is something that we are still getting to accept as a society. It’s not something that [goes like] “I’m gay and that’s who I am, right”, or “I’m LGBTQ+, and that’s who I am”. We have to go through that introspective space, we also have to go through what do I look like, because there’s an expectation from society around how you present yourself, what does queer look like to the world? … It took me a long time to get to a place where I accepted that this is what feels right for me, because probably when someone sees me I might not look stereotypically gay, and actually that’s okay.”

“And I remember walking into this room and always being really struck by this dress and having this real emotional reaction to it. I was thinking about the Little Britain characters, and how much when we look at the images that I had of trans women that were presented in the noughties, something obviously drew those creators to – when they were making fun of trans women – to do it through Victorian style dresses as well. And there was something about it that seems to speak of trans femininity, and maybe it’s the over-the-topness, maybe it’s the fact that it feels a bit over the top in terms of its expression that then feels not attainable, but enough of a fantasy that you are not picturing yourself in it, which is really important when you’re not out, because you are allowed to enjoy expressions of femininity as long as they are in no way connected to you. … Femininity is often under-respected, often, even if we have a feminist character, it will be them ripping a part of their dress off, and we’ve got to interrogate our feelings around why. It’s okay to be feminine, it doesn’t make you less feminist, it doesn’t make you less valuable, and I feel like part of why I want to talk about this dress is to say that.”

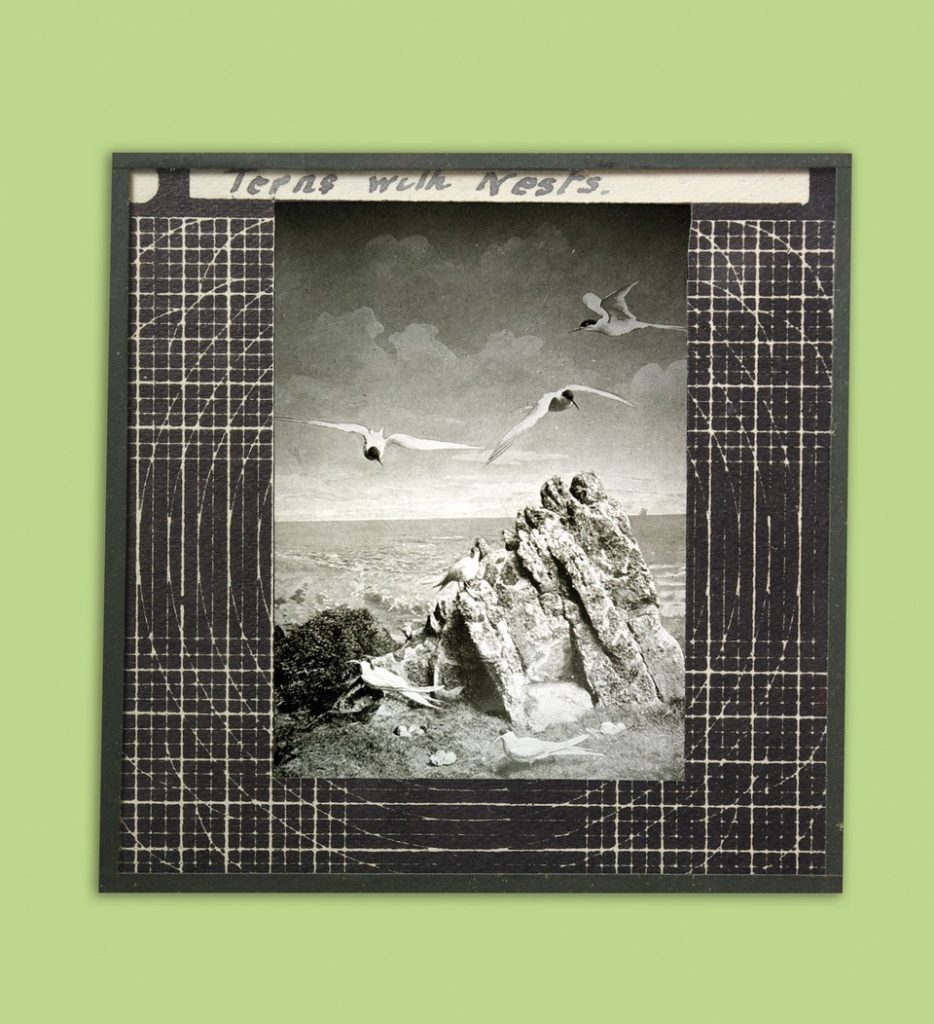

“I’ve chosen Terns with Nests, which is a magic lantern slide from Alfred Rhoden, and it’s part of the magic lantern slide collection. It is a captured seascape with a rugged rock, some terns, which are silver and white birds with a black head and a long beak, circling around a nest at the base of the rock where you can see they’ve got eggs. And the photograph here of the terns with nests is from the Devon coast. It reminded me of the particular crags and rocks and the birds in particular of where I grew up in Dublin beside the sea. … I would say that I am a spiritual person, but that is intrinsically linked with nature and the natural world around me, and I think you’d probably find the same in a lot of queer people, you know, where we can’t or haven’t, growing up, made the same connections with establishments, and with the same standard external sources of family that you might have through community, through village, through parish, through church or religion, so we found other connections, either through found family and friends, through connections with nature, connection with, in my teenage years, the moon, just looking for this sense of connection and identity somewhere else. … These birds, that coastline, those rocks, and that connection with sea and water, it’s a really fundamental part of who I am.”

“Handcuffs spoke to me about the ongoing relationship I’ve had with how I feel about the law, the government, the police, and the relationship with the queer community. I came out as a lesbian in the 1980s at a time when the relationship between the queer community and the police was really strained and, really, it was a really difficult time. … I think it was about fighting any kind of oppression and injustice in the end, and for me personally in terms of being a youth worker, which is my chosen profession, I’ve seen the injustice young people face, too, with transphobia, homophobia. So, I think the fight became broader than just how I started out, which was fighting, being part of the peace movement, it was like we just became anti-oppression. … I do hope that anybody from the queer community – anybody from the LGBTQ community for those that don’t like the word queer – looks at the object and understands why I’ve chosen it and thinks about how their own lives have been impacted by oppression and looks at what part they can play in making life simpler for the LGBTQ community going forwards.”

“The object I’ve chosen out of the collection is a chasuble; for all intents and purposes, a very ornate garment worn by priests in the moment where they would move from their ordinary clothes into a kind of sacred or religious ceremony. … I think within a medieval kind of Christianity what I’m really excited about is the uncharted sense of gender and sexuality in general that is so vastly different from the kind of image of heteronormativity under capitalism as opposed to this deep, murky medieval religious context. … I mean, I don’t want to speak for people but it’s a universal experience of queerness, where you’re, kind of, in this process of casting off the things that have been put on you to move into this space that is an uncharted expanse of like symbols and history and becoming that feels very spiritually significant. … The knowledge that all objects can be undone and be undone in order to take away the dry dust that archiving puts on these objects and that they have a life and try and imagine or put back together the life that they may have had outside of the museum.”

“I selected the butterfly. … On a personal level for me, you know, I came out at the age of 17 after I was brought up in a really strict religious family; coming out at the age of 17 felt like I was coming out of my cocoon, that I could be myself. … My life has been challenging on all sorts of different levels, dealing with religion and dealing with my parents rejection and conversion therapy and becoming an alcoholic and dealing with all that and thankfully coming to my senses at the age 26 and then doing the rehab thing. But if somebody had said to me, you know, during the recovery that in 26 year’s time, you’re going to be the CEO of an LGBT charity, I would have just laughed in their face. … I am the CEO of the Intercom Trust, and we are the regional lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans + charity, and for me seeing clients coming up, I have been here for 16 years now, and seeing clients come in when they are kind of just bursting through their own cocoon and seeing them change and grow, becoming the beautiful people that they are, flying off and getting on with their lives. … We’re all beautiful people and, you know, we come out of our cocoons at whatever age that might be; the client groups that we work with … young people [and] their families, and the oldest client that I worked with came out as a trans woman at the age of 84 in a small town in Cornwall … how beautiful is that? “

“I’ve chosen a bronze age arrow flint from Fernworthy, which is on Dartmoor. It is triangular, and you can kind of see all of the notches on it from where it’s been carved, and there’s two little indents at the bottom. … I know the area of Fernworthy well, and Fernworthy Reservoir, which is where the archeological dig that found this arrowhead was done. And I actually went to Fernworthy for Solstice, because I’m a Pagan, and so the kind of Celtic Pagan ceremonies and dates are really important to me to celebrate. … I identify as Pagan, and I think like a lot of queer people that I know, it’s sort of been their way to find spirituality when a lot of other religions might be homophobic or transphobic or things like that. For me, it’s kind of like my spirituality. … I am a history nerd, not all queer people are, but I think from the Pagan aspect, and the Pagan people that I celebrate, the past is important. For a lot of people, Dartmoor is an important spiritual place, so I think it would be interesting from that point of view.”

“I have chosen a bronze sculpture by Barbara Hepworth. It has a hole in the middle, and it has a very different texture, and so there’s this opening that almost makes you want to discover the object and look inside. The reason I’ve chosen it though is because it’s called Zennor, and that is a place that I have a very strong connection with, so it’s really that link to Zennor, which is a very small place in Cornwall. There is a writer called H.D., who was an American poet, and another writer called Bryher – this is obviously a pseudonym that they chose, they named themselves after one of the Scilly Isles. H.D. and Bryher were in a lifelong open polyamorous relationship, and they met in Zennor. You can imagine them meeting and talking about their work and falling in love in that space and going on this beautiful coastal walk. … I like this idea of almost an unexpected opening that gives you access to something that you might not previously have seen as something that is for you or that belongs to you, and so for me it is an unexpected opening up of a relationship that I can have to the South West through that queer history. Any object might have a queer or trans or non-binary history or resonance, and we just need to have the knowledge, we just need to have the information and background knowledge to reframe those objects.”

“I chose a wolf bone, it’s a leg bone. I wrote my MA dissertation on werewolves as a transmasculine metaphor, so I was interested in this wolf connection. I think about werewolves as this kind of stepping stone connection in-between man and beast that destabilises that boundary. … So, I’m really interested in this idea of alternative sites of representation, sort of non-canonical. I think you can often feel like when you’re talking about trans things and looking at representation that you have to show this easy narrative, this linear narrative that’s digestible and understandable to cis people, because you don’t want to look complicated or messy, and I think that that can make working through transness yourself really difficult because you have no outlet. … It’s quite empowering, I think, to go around and be like, well, this might not be a history that is going to go into a history book, but this speaks to me and as a person who will, you know, in time also be history that kind of dialogue is really exciting.”