By Lucy Allan-Jones

Judith Ackland (1892-1971) and Mary Stella Edwards (1893-1989) were lifetime partners, and a selection of their artwork now belongs to RAMM. On the Queering the Museum Project and elsewhere, researchers have begun to uncover more about their relationship with one another, and with the Southwest.

Of particular interest is their cabin in Bucks Mills, North Devon, which the two visited every summer for the best part of 50 years. A whitewashed one-up-one-down on the edge of a cliff, the cabin was first acquired by the Ackland family in 1913 and provided Mary and Judith with somewhere to nurture their creative energies as well as their love for one another.

It is important to respect the fact that the two never publicly defined themselves as lesbian, or gay, even when they could’ve done given the wider availability of these terms in the second half of the twentieth century. What is clear in letters between them, however, is a love that exceeds the ‘normative’, and that we can, as such, include under the queer umbrella.

In 2008, the cabin was gifted to the National Trust and remains almost untouched since the women closed the door on it for the last time. A 360° tour available on the Ackland and Edwards Trust website reveals paint stored under the bed, crockery on the shelves, and a watercolour hung up to dry. The significance of the cabin as a site of queer heritage was explored in a podcast series commissioned by the National Trust called Prejudice and Pride, where it was used to discuss the concept of creative retreat.

In the podcast, writer and academic Will Eaves defines ‘creative retreat’ as “a line of defence or retreat from social pressures, from the liveliness of your social environment, from your day to day duties, and it represents an opportunity to get in touch with who you really are and what you really want to do”. Put simply, a creative retreat provides a place where social pressures, including cis-heteronormative ones like marriage, are alleviated, and failure to conform to them is accepted, , understood as generative rather than antisocial.

For Judith and Mary, the annual retreat to Bucks Mills provided them with the space to fail together. Somewhere they could move toward one another, and away from the societal and familial obligations attending them in their everyday lives. What they created in their retreats to the cabin was not just artistic, but relational too.

Their position on the edge of the village, and proximity to the beach, also seems to have inspired a relationship with the natural world that exceeds the observational. As such, I think it is useful to view their relationship and their art through the concept of queer ecology. Queer ecology is a movement toward understanding all living things as interrelated, eroding divisions between natural and unnatural, human, and non-human, and the valuable or valueless judgments that accompany those binaries. As part of this, queer ecology also exposes the heteronormative assumptions we have historically made about nature, favouring instead an approach in which the complex relations that exist between all life are understood.

By analysing the composition of a few of Judith and Mary’s paintings, we can see traces of a queer ecology emerging. It gives us a way to understand them, and their relationship with Bucks Mills, that holds all relational possibilities open, in any combination of romantic, platonic, or sexual. There is no need to scrutinise their relationship in the interests of finding a label that ‘fits’, if we can adopt a lens that recognises the failure of all labels, and allows their relationship together to endure as whatever it was.

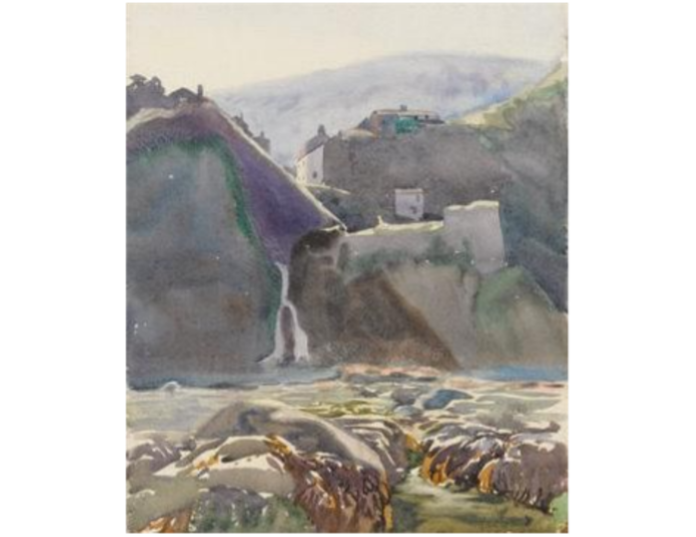

In this watercolour of Judith Ackland’s titled “The Cabin from the Shore” (1941), we see the landscape empty of people, with seaweed and rocks in the foreground, and hallmarks of civilisation (the cabin and the village) in the background.

The perspective is from somewhere on the beach, closer to the ecosystem of seaweed and rock pools than the human-dominated one at the top of the cliff. The cabin, however, sits on the threshold of the two, tied neither to the village nor the beach. It appears to be almost part of the cliff, but the colour of the rock matches the rest of the village buildings. The cabin, and by extension the people inside, are captured in an environment where lots of different relations are possible. Against the greys and browns of the rock, the green and purple seam running from the beach up to the village looks almost supernatural by contrast, capable of traversing both geographical and man-made distinctions to draw every part of the painting together.

Mary Stella Edwards’ watercolour “Paddling in the Sea” (ca. 1940-1979) reverses the perspective, and we see a view of the beach from the cabin.

A much more colourful scene, there are several groups of people on the sand and in the water. But the further the people are from the village and the cabin, the less vibrant the colours get, and the closer to the colour of the sea and the sky they become. The distinct humanness of their bodies gradually collapses as they are swallowed by the blur of sea and sky.

Finally in this watercolour “Left by the Tide” (1958-1960) by Mary Stella Edwards of seaweed draped over rocks on the beach, what is striking is how it foregrounds the seaweed in the same way a person might be in a portrait. It stands, almost bipedal, posed on the rocks with a visceral red agency, commanding the attention first of Mary Stella Edwards, and now the viewer in her rendition of it. Again, the natural comes into focus, and a new kind of relationality is opened in the compositive dynamics of the painting.

The medium for all three paintings is watercolour, the fluidity of which, according to Edith Dormandy, “makes it seem to me an excellent [medium] for slippery subjects, such as queerness. Watercolour in its broadest definition of pigment suspended in watersoluble binder” (“Bodies in the Archive: Is There an Alternative History of Watercolour?”). In many ways, I think Judith and Mary’s relationship to each other and to Bucks Mills reflects the medium within which they chose to express it. Two pigments brought together and made soluble by the sea, and bound permanently by it in the art that has outlived them.