The Royal Albert Memorial Museum holds a number of seaweed and algae specimens collected by the early Victorian botanist Amelia Warren Griffiths (1768-1858). Revered by many of the leading experts of her day, Griffiths was so renowned for her scholarly expertise that several seaweed specimens were even named after her, such as the Griffithsia and Furcus Griffithsia. Whilst Griffiths published relatively little in her lifetime, she maintained a constant correspondence with experts such as W. D. Harvey, who dedicated his seminal 1849 text British Marina Algae to Griffiths.

Seaweed collecting had become a popular activity for Victorian women. In an essay entitled ‘recollections of Ilfracombe’, the author George Eliot described her fascination for the intricate algae forms, noting ‘these tide-pools made me quite in love with sea-weeds’. Nevertheless, many raised an eyebrow at the sight of women wandering alone on the edges of the beach, an occurrence at odds with the Victorian expectation that middle-class women should always go about accompanied, in order protect their modesty.

Griffiths, however, was not entirely alone in her efforts to collect and preserve seaweed specimens across the Devon and Cornish coast. At her side was Mary Wyatt, owner of a pressed plant shop in Torquay. Wyatt had originally worked as a servant in the Griffiths household, before developing a close friendship with Griffiths and setting up a business independently. Together, they scoured the coast, searching for specimens, and Wyatt eventually published the results of their findings in Algae Danmonienses, a multi-volume compilation consisting of specimens from Devon and Cornwall. Their work, in other words, was an active collaboration, as they scrambled across rocky shores in cumbersome skirts, compared notes and exchanged specimens in real time.

This intimate collecting history rewards further consideration. At first glance, the story perhaps appears unremarkable. Two female friends working together does not immediately suggest romantic involvement, an idea particularly at odds with our received notions of the Victorian period. If we press further, however, it becomes evident that the early Victorian period had a number of such close companionships, framed around the common activity of collecting. In her book, Sister Arts: The Erotics of Lesbian Landscapes, Lisa Moore has drawn attention to the popularity of such activities, suggesting that they were a way of celebrating partnership and companionship amongst women. Might these ‘friends’, and their activities, actually evidence a form of intimacy that contemporary viewers would call queer? Whilst words like ‘lesbian’ and ‘queer’ did not then exist in the way that we use them today, they can still be helpful terms for understanding a longer history of same-sex desire. Moore argues that the ordering of natural history in a domestic setting, like the arranging of algae within a scrapbook, was one way of expressing love for women, and one that has often been overlooked.

To understand the history of queer identity, therefore, we might need to reconsider how we look for evidence of same-sex relationships. The story of Griffiths and Wyatt roaming the coasts and working together, in fact, might be a tale belonging to LBTQIA history.

Queer Objects, Queer places

The queerness of seaweed has been recognised for a long time. In 1898, the writer and women’s rights activist Edith Ellis published her first novel, Seaweed: A Cornish Idyll, which narrates the tale of a forbidden love affair and its consequences. Ellis was a queer author who argued for the creative superiority of the ‘invert’, an umbrella term then used to describe gay and gender non-conforming people. The novel, set in rural Cornwall, is framed around collecting seaweed, as Janet, wife of ex-sailor Kit, leaves the house for long periods of time, on the pretext of gathering seaweed to make an ointment for her husband. Kit’s mother and her friends in the village are suspicious of the activity and of the supposed benefits offered by the seaweed. They see seaweed as a symbol of deceit and treachery, linking it to witchcraft, ‘nothin’ but pap to stop up Kit’s mouth wi’, an object that threatens the stability of the normal family unit. Seaweed, in other words, becomes a byword for forbidden activities, a symbol of female transgression. Janet gathers seaweed in order to be able to see her love. As collecting becomes a synonym for female desire, could we also read a subtext of same-sex desire in the novel?

Kit reflects on his marriage with Janet during her long periods of absence. He is frustrated that he is unable to offer her sexual satisfaction due to complications resulting from an accident at work. He tries to explain this to the village’s new curate, who is horrified at the suggestion that women might have sexual desires: ‘but, my good man, you don’t suppose for one moment that women have animal passions like ours[?]’. Kit is clear that this is the case, and the curate interrogates him further,

Do you seriously meant to imply that you have some idea of letting your wife – ahem! – cohabit with another man while keeping up a semblance of a relationship with you?

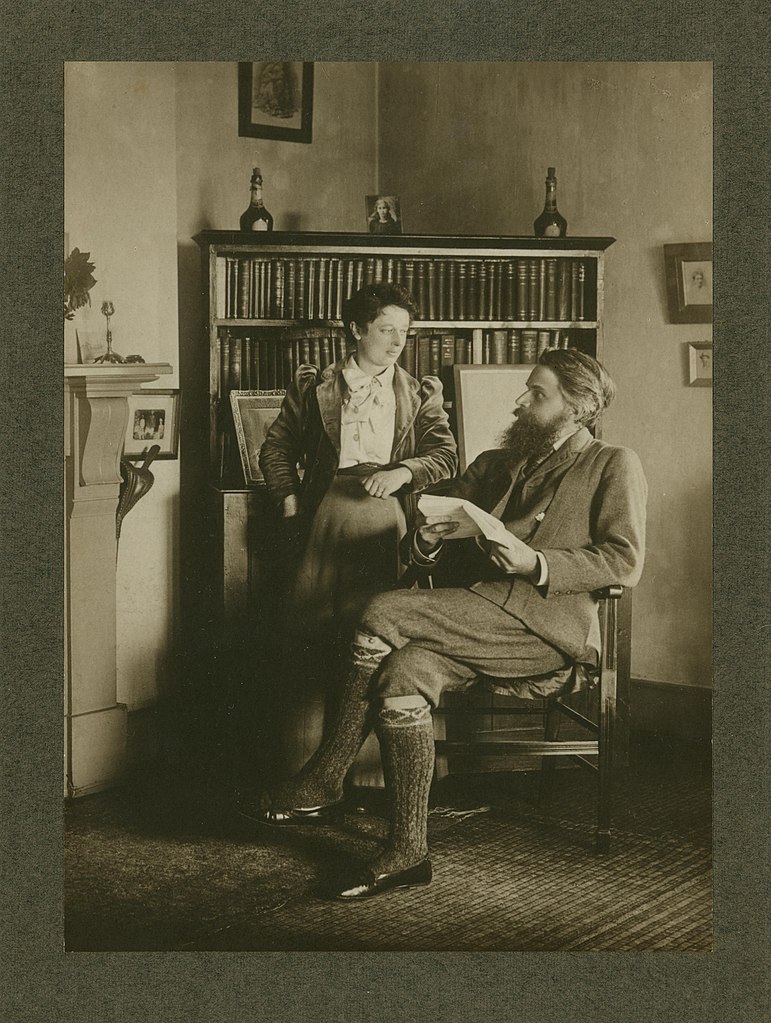

The idea has an interesting connection to Ellis’ own life. Married to the prominent sexologist Havelock Ellis, the pair were in a non-romantic life partnership, built on the values of mutual understanding and respect. It is commonly suggested that Edith is ‘Miss H’, an example of the ‘female invert’ used by Havelock in his groundbreaking study Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897). Whilst Edith had taken a deep dislike to Havelock on first meeting, after a chance encounter in Cornwall in 1890 the pair developed a deep friendship and married the following year. The relationship was ultimately an important source of great companionship for both. This type of relationship is matched in Kit and Janet in Ellis’ novel. Whilst other characters encourage Kit to restrain Janet, his mother even claiming that ‘a woman must be captained same as a ship’, Kit and Janet work out a relationship based on their own needs. The story’s queerness resides in its presentation of a fulfilling relationship outside of social mores, in ways that people around the couple struggle to recognise.

The portrayal of disability suggests a further connection to queer history. At the beginning of the twentieth century, homosexuality and gender non-conformity (lumped together as ‘inversion’) were considered to be a form of disability, a so-called defect of development. Both disability and queerness would often result in partial or total exclusion from society; Ellis, however, campaigned for the acceptance of those who felt, in her words, an ‘alien amongst normal people’. These intersections between disability and queerness – in particular the shared experience of exclusion – have been powerfully reclaimed thanks to the pioneering work of queer disability activists over the past fifty years. Ellis’ novel, despite its use of outdated language, may be reread as an early effort to counter the ableist and prejudiced assumptions prevalent in her society, through its celebration of a relationship built carefully around the sexual and physical needs of both individuals. This type of relationship was exactly what Havelock and Edith aimed to build together.

In the same period that Ellis was writing the novel in Cornwall she met the artist Lily Kirkpatrick, and the pair would be lovers until Lily’s death in 1903. Cornwall was an important site of refuge for many queer writers at the beginning of the twentieth century, who considered the place as almost foreign to England with its apparently wild and untouched landscapes. The trans writer Bryher, for instance, based their name on the island ‘Bryher’ in the Isles of Scilly. They introduced their eventual life partner, H. D., to this “personal” place, and the couple spent much time in Cornwall, where Bryher was able to show H.D. their “boyhood”, an experience not acknowledged by others at the time of their childhood. Similarly, the queer writers Michael Field (a pseudonym for the couple Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper) found religious and sensual value in the landscape on their holidays to Cornwall a few decades earlier. Common to these writers is a deep appreciation of place, a quasi-spiritual connection to the nature around them that allowed them to realise who they are and what they desire, beyond the expectations of their society.

In 1938, Daphne du Maurier published Rebeccca, a gothic novel set in Cornwall. The novel plays on the unfamiliarity of Cornwall that so many queer writers found attractive, suggesting it is a place still inhabited by ghosts. Cornwall is a kind of space beyond, a land at the edge of the sea. Seaweed marks the final boundary between the ground and the water, ‘the woods came right down to the tangle of seaweed marking high water’. In this sense, it is an object between things that is constantly changing, both in and out of the water, ‘as the slow sea sucked at the shore and then withdrew, leaving the strip of seaweed bare’. Seaweed is the final frontier between the known and the unknown.

Seaweed seems a particularly beautiful object for queer history. It defies classification, the word referring to the thousands of forms of algae that litter the water floor. A weed of the sea, it officially lacks any formal definition, and yet it is nevertheless essential for the eco-system of the sea. Some writers, like Timothy Morton, have suggested that ecology, free of hierarchical structures and order, is a queer object of study. According to queer ecology, nature is fundamentally queer because it undermines any of the certainty of human control. Random, erratic, aesthetic, ecology teaches humans the capacity of queerness.

Preserved almost translucent on the pages of Griffiths’ collection, the intricate networks of veins threading across blades of seaweed suggest a hidden life of non-human activity. The collection is unexpectedly beautiful. Considering such unexpected objects, stories and places, a rich network of queer histories is revealed to be threaded through the museum’s collection.

Further reading

Clare, Eli. Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation. (Duke University Press, 2015)

Ellis, Edith. ‘Seaweed: A Cornish Idyll’ (London: The University Press, 1898) – available on archive.org

Moore, Lisa. Sister Arts: The Erotics of Lesbian Landscapes (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

Morton, Timothy. ‘Guest Column: Queer Ecology’, PMLA 125.2 (2010): 273-282.